FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Toronto, ON, September 3, 2019 — Circuit Gallery presents new work by gallery artist Akihiko Miyoshi. In this latest project, Miyoshi pushes his interest in the aesthetic space of digital and networked structures to consider questions of affect and representation, working to find a visual language that conveys the mediated experience of seeing through lenses and on screens.

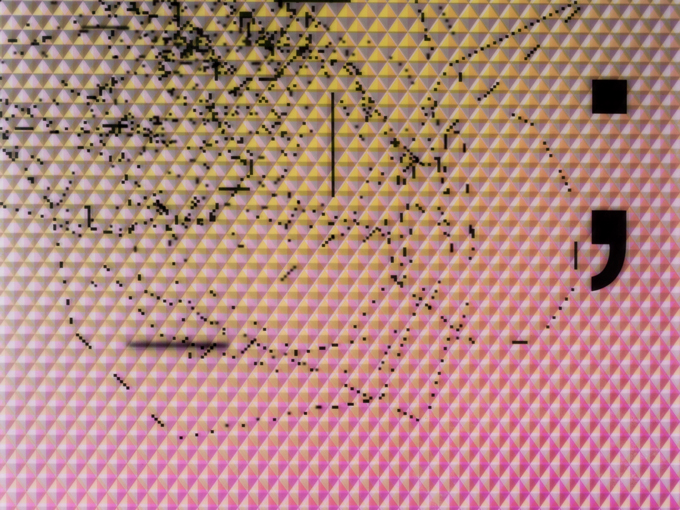

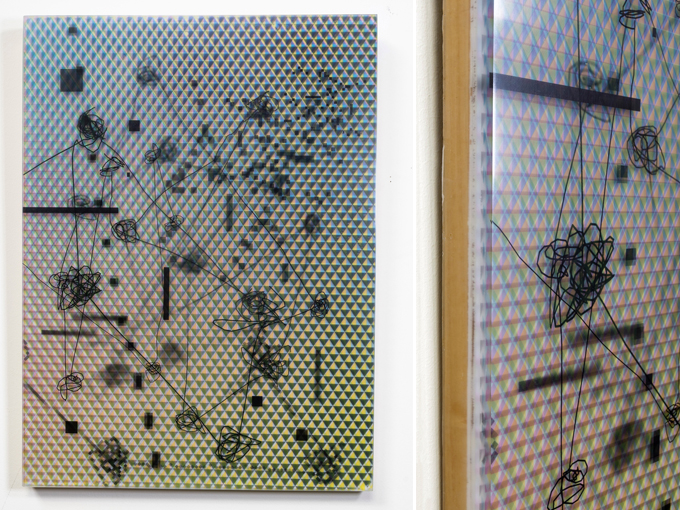

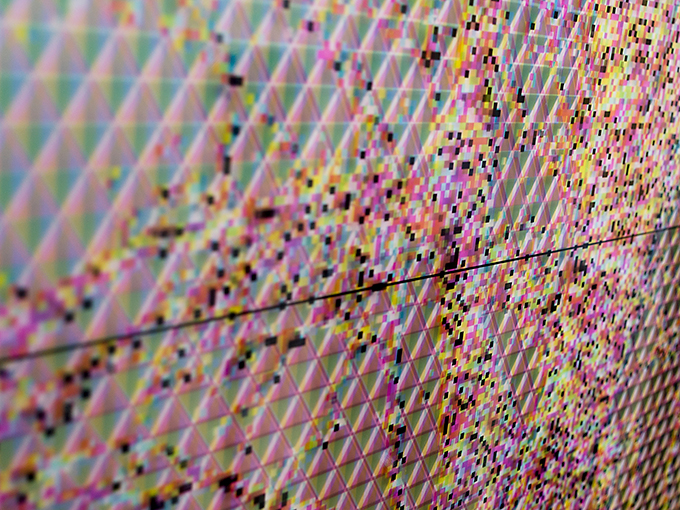

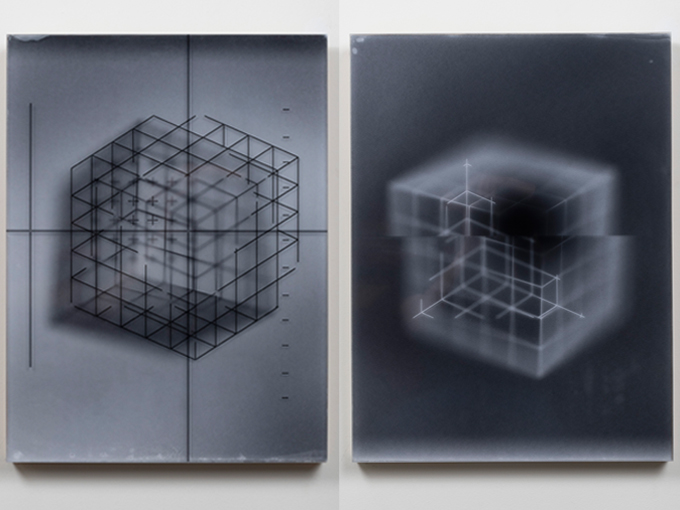

The sixteen decidedly analog and material new works presented in Through Lens and Screen—what Miyoshi simply calls ‘Resin Paintings’—are comprised of thick layers of resin and inkjet pigment, built-up or sandwiched together to create unique and ‘active’ images, images that are constituted by looking through the layers from a given position in space. The resin here becomes a substrate that both resembles and takes us closer to the experience of looking at screens or through viewfinders.

As Miyoshi explains—“I consider the work phenomenological and active. This active quality is important. It is a departure from the traditional static image based on paper or canvas. This allows for a new visual language that I believe is suited to invoke the digital and the network, both of which do not have, in and of themselves, a material basis.”

Miyoshi’s new work, which he categorizes under the subheadings ‘Networks,’ ‘Screens, Monitors and Viewfinders,’ ‘Theory,’ and ‘Computer Drawings / Code Paintings,’ can be seen in relation to the debates in digital aesthetics around the possibility of representing networks. This is how new media theorist James J. Hodge frames it in his essay ‘New Maps, New Poetics: New Works by Akihiko Miyoshi’ that accompanies the exhibition:

All images of the internet look the same! So runs the complaint voiced by media critic Alexander R. Galloway in his 2012 book The Interface Effect. In his artist statement Akihiko Miyoshi cites Galloway’s discussion of the ostensible ‘unrepresentability’ of networks as seminal for his recent work. As Miyoshi notes, Galloway’s provocation has two parts: all images of the network look the same; and even at this late date in the twenty-first century we still lack a poetic or aesthetic vocabulary for imaging and imagining networks. Guided by a dual interest in both the material infrastructure of technology as well as the paradoxically sensual and intangible aesthetic experience of the internet, Miyoshi’s recent works […] provide a timely and sophisticated set of artistic responses to Galloway, and, by extension, to fundamental issues at the heart of contemporary visuality, technology, and experience.

Akihiko Miyoshi: Through Lens and Screen runs September 5 through 28 at Circuit Gallery @ Prefix ICA, in Toronto.

BIOS

Born in Japan, Akihiko Miyoshi received his MFA in photography in 2005 from the Rochester Institute of Technology after leaving a PhD program in Electrical and Computer Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University to pursue art. Miyoshi is currently an Associate Professor of photography and digital media at Reed College in Portland, Oregon.

Miyoshi’s work explores the intersection between art and technology most frequently dealing with issues surrounding representation. His exhibition record includes shows in Portland, New York, Los Angeles, Rochester, Pittsburgh, and Toronto. He was named the International Award Winner of Fellowship 12 at The Silver Eye Center for Photography in Pittsburgh PA, and the finalist for the Betty Bowen Award from the Seattle Art Museum in 2012 and Aperture Portfolio Prize in 2013. Miyoshi received a Hallie Ford Fellowship in 2012. He is represented by Circuit Gallery, Toronto.

Artist Page: Akihiko Miyoshi

James J. Hodge is Associate Professor in the Department of English and the Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities at Northwestern University. His essays on digital aesthetics have appeared in Critical Inquiry, ASAP/Journal, TriQuarterly, and elsewhere. His book Sensations of History: Animation and New Media Art will be published this October by the University of Minnesota Press.

Akihiko Miyoshi

Through Lens and Screen

September 5 – 28, 2019

Circuit Gallery @ Prefix ICA

401 Richmond Street West, Suite 124

Toronto, ON, M6R 2G5

[ Google Map ]

Gallery Hours: Tuesday – Saturday, 12:00 – 5:00 p.m.

Visit Circuit Gallery for more information and to see more images:

www.circuitgallery.com/exhibitions

ABOUT CIRCUIT GALLERY

Circuit Gallery specializes in contemporary photography. Established in 2008 by Susana Reisman and Claire Sykes, the Toronto based commercial gallery represents both emerging and established Canadian and international artists.

Web: www.circuitgallery.com

Email: info@circuitgallery.com

Phone: 647-477-2487

###